KALA 03: Ulantaga, Paper as Practice in Balinese Life

by Marlowe Bandem

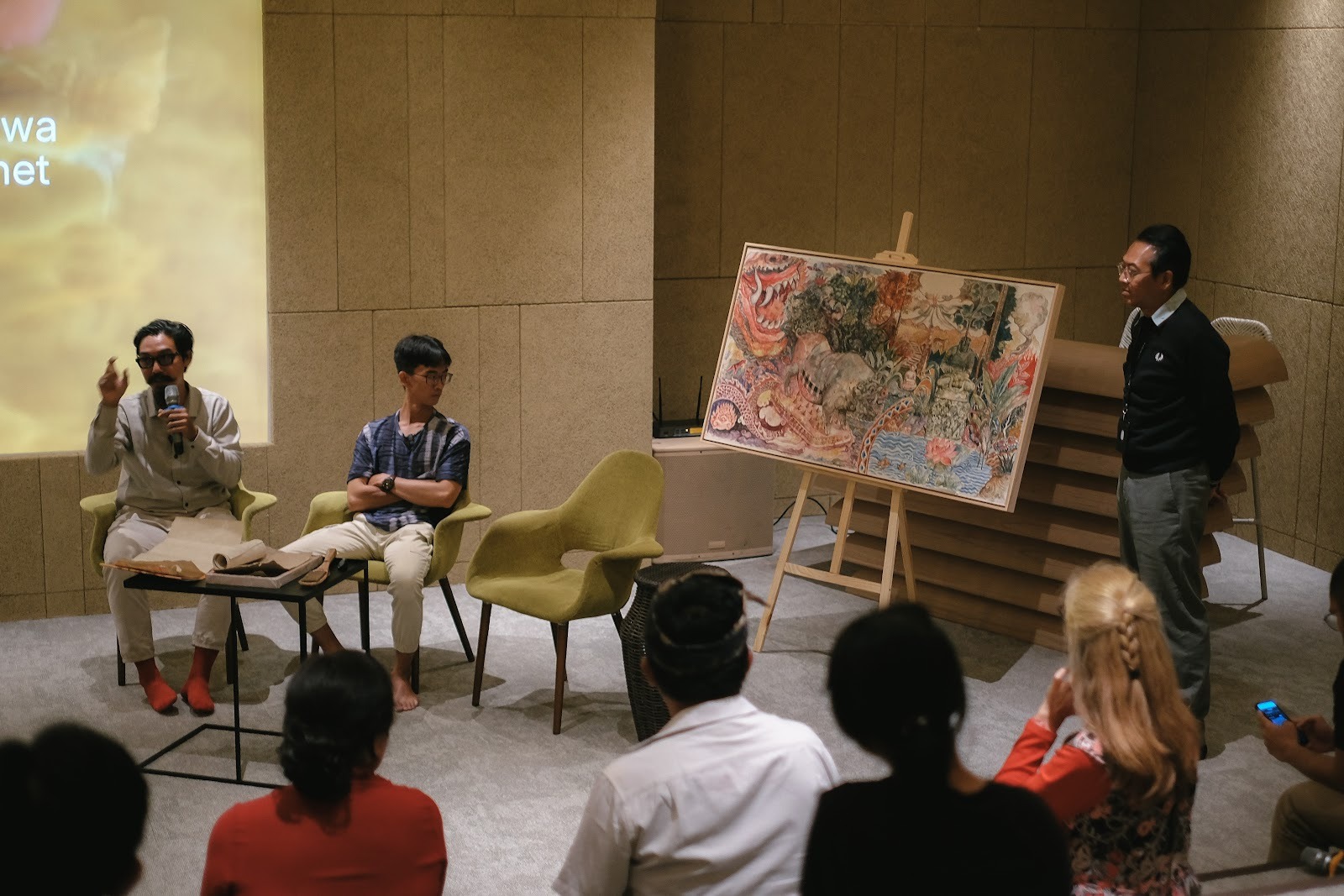

On Thursday, 27 November 2025, the SAKA Museum Auditorium hosted the third edition of KALA (Knowledge, Artistry, Legacy, and Awareness). Titled Ulantaga: Paper as Practice in Balinese Life, the session explored mulberry bark paper, known as daluang, as an enduring medium that links heritage, ritual, and artistic practice in Bali.

The conversation brought together two speakers in a gentle but powerful tandem. Aryatama Nugraha and Dewa Purwita Sukahet each approached daluang from a distinct angle.

Arya, from Studio Kreasi Dluwang, spoke as a practitioner and papermaker. He is widely recognised today as one of the most dedicated makers of daluang in Bali. Largely self-taught, he has refined his technique through years of experimentation. His journey is also shaped by family. Growing up, he observed the worlds of paper and printmaking through his father, graphic artist Devy Ferdianto.

Dewa Purwita Sukahet, in contrast, approached daluang as a researcher, writer, and visual artist who reads paper as a cultural trace. An established artist and author focusing on visual culture and art history, he is also a co-founder of the Gurat Institute.

That evening, the auditorium filled with people from many corners of Bali’s cultural world. Young design students and museum practitioners shared rows with artists and curators, while a few guests clutched small sketchbooks, ready to take notes. Among them was Goenawan Mohamad, the poet and essayist who now spends much of his time in Bali, moving between writing, painting, and quietly observing the island’s shifting rhythms. Nearby sat Ibu Ayu Dayu Sutariani, the director of Museum Bali. Close by, her colleague SAKA’s director Judith Bosnak listened attentively and occasionally leaned over to exchange brief remarks as interesting ideas began to take shape.

Moderated by Marlowe Bandem, the session opened by naming a small tension that quietly structured the afternoon. Daluang is often spoken about as a “traditional medium,” yet its meanings shift depending on who touches it, whether priests, artists, conservators, farmers, or archivists. As more Balinese artists turn toward daluang today, the question is no longer only how to make it, but how to hold it. What kinds of care, knowledge, and responsibility are required when a ritual material becomes an artistic surface? For this edition, painter Wayan Suja lent his work Titi Kala Mangsa (Once Upon a Time), made with natural Balinese pigments applied onto daluang and mounted on canvas. The work offered an image of bark paper as a bridge across time and across forms.

Arya began by taking the audience far beyond Bali. Long before cotton, silk, or factory-made paper, he explained, ancestors across the Asia-Pacific were already using bark as clothing, writing surfaces, and a base for artistic expression. The beating of bark into cloth belongs to a shared Austronesian heritage, with traces stretching across vast geographies from Madagascar in the west to Easter Island in the east. In that sense, daluang does not arrive as an isolated Balinese artefact. It belongs to a much older family of material intelligence shaped by fibre, water, pressure, and time.

He then brought the story back to the bark itself. Daluang, he explained, is made from the inner bark of the paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), and there are two broad approaches to producing paper from bark. The first is the beaten-bark method and the second is the pulp-based method. In the beaten-bark method, softened strips of inner bark are hammered repeatedly until they fuse into a single sheet. The result is often thicker and more cloth-like, with visible fibre patterns, soft edges, and an organic surface that can be uneven in texture and colour. In the pulp-based method, the bark is broken down into a watery pulp and formed on a screen, producing paper that is typically thinner, flatter, and more uniform, with cleaner edges and a smoother, lighter, more consistent appearance. It is closer to what many recognise as conventional handmade paper.

What made Arya’s account compelling was how quickly the technical became ethical. A sheet of daluang is not simply “made.” It is cultivated, harvested, softened, beaten, dried, and handled through a chain of small decisions. The process is slow, prone to human error, and difficult to scale. Yet that difficulty is also its meaning. It forces patience, attention, and a different tempo of making. In Arya’s hands, the work is as much agricultural as it is artistic. It is rooted in the care of trees and the labour of transformation, so that the paper can re-enter everyday life rather than remain a museum memory.

Dewa’s presentation shifted the room from technique into language. He began with a careful correction. In Bali today, he noted, the terms daluang and ulantaga are often used interchangeably, even though they refer to different things.

Referring to Kamus Jawa Kuna Indonesia by P. J. Zoetmulder and S. O. Robson, widely regarded as the authoritative dictionary of Old Javanese, daluang is defined as a bark-based material often associated with the bark-cloth tradition. Ulantaga, which also appears as walantaga, refers instead to ceremonial pennants and streamers. These are objects closer to kober (flags), and umbul-umbul (banners) that appear in ritual contexts, including ngaben or cremation. Put simply, “kertas daluang” is the more accurate phrase for bark paper, while “kertas ulantaga” is, strictly speaking, a mistaken usage.The correction was not pedantic. It opened a deeper point about how words carry ritual images inside them. To ground the distinction, Dewa referenced a passage from the lontar manuscript Sumanasāntaka(Part X) and lingered on a line that made the sacred feel almost architectural.

sĕlā ni pang i cāmaranya hawan ing kukus asĕmu walantagângadĕg,

“… gaps between the branches of the casuarina trees formed a path through which streamers of smoke rose …”

Here, walantaga is not a paper label at all. It is a streamer of smoke rising through a corridor of branches. It marks an in-between passage where the human realm begins to give way to the sacred. The term names movement, transition, and departure. For Dewa, this was precisely why language matters. If a museum is trying to revive a material practice, it must also revive the accuracy and the poetry of the terms that surround it.

The discussion grew even richer when Dayu Sutariani shared a recent encounter in Denpasar. A community keeps what they describe as a prasasti, a recorded historical text, written on what they call “kertas ulantaga.” The document mentions the kingdom of Badung and may date back as far as the fifteenth century, though she stressed that proper research and rereading are still needed. Still, the story sparked an exciting possibility. Bark-based media may have played a transitional role in Bali’s writing history. It may have bridged shifts from stone to copper to lontar at a time when wider exchanges, including contact with China, were reshaping the island’s material world.

Questions from the audience then turned toward the creative potential of daluang. Sekar Pradnyandari, a young writer, asked what makes it unique for artists today. Arya and Dewa answered in a shared register. Daluang is rare, it has a distinctive surface, and it challenges the artist. It is rare because the process is demanding, from cultivation to harvest to treatment, and it requires patience and skill. Its texture is delicate. Touched by hand, it does not feel like ordinary paper but closer to silk, which is why some refer to it as “silk paper.” It is also slightly translucent, and when brought into printmaking, it can produce surprises that are difficult to predict in advance. These qualities are exactly what draw artists toward it, as with Wayan Suja’s painting, where gradual watercolour-like layering demands time, restraint, and care.

Another thread that surfaced in the room was conservation. How does one exhibit such a fragile medium without damaging it? A participant spoke about museum principles, especially reversibility, and argued that conservation should avoid permanent fixes. It should allow works to be opened, adjusted, and cared for over time. Adhesives must be stable and pH-controlled, while pigments, especially natural ones, are vulnerable to ultraviolet light. The comment carried the conversation into a practical register. If daluang is to return as a living practice, it must also return with the knowledge of how to preserve it.

Devy Ferdianto returned to a more public question. If daluang is so closely tied to Balinese culture, why do so few people recognise the tree today? He suggested that sacred artefacts often become distant from their communities. People know their function, but they do not understand their origins. He compared it to prada (the decorative gold (or metallic) leaf finish used in Balinese arts, especially on textiles and ceremonial objects) in Balinese culture, which is highly visible in ceremony yet unclear in process for most people. His comment carried an implied challenge for institutions. If knowledge remains hidden, it cannot be sustained. With SAKA’s proximity to AYANA Farm, he suggested, the museum could offer not only theory, but encounters. Lectures could be paired with demonstrations, planting, and hands-on learning that restores intimacy between people and material.

The evening closed on a quiet note, delivered by Goenawan Mohamad. He mentioned that his first real encounter with daluang came through Arya. Then, almost gently, he widened the lens. What he finds distinctive in Bali, he reflected, is a dynamic continuity. The past is not simply archived. It remains in circulation and reappears in conversation, ceremony, and craft as part of contemporary life. That, to him, is Bali’s gift. It is a living continuity of memory and achievement. His hope was simple and direct. Let this not stop at admiration or talk. Let it continue as shared knowledge, and let it continue as action. Plant the trees, sustain the practice, and return daluang to life not as a trend, but as local wisdom that can stand on its own again.

If this conversation sparked something, whether curiosity, recognition, or a sense of responsibility, let it be a beginning. KALA will return with new questions, new materials, and new voices.

Until then, SAKA Museum remains open as a place to keep learning, looking, and listening. Join us for the next KALA, and come to SAKA to encounter Bali’s living archives that are still in motion and still being made.

.jpg)